I’ve mused in many articles about the reasons anyone would do something as completely barking mad as writing… and I’m not the only one. Analysis of the writerly life can be delightfully variable, as witnessed by the fat that everyone has a different take. Isaac Asimov used to consider writers as a species of supermen, an activity not everyone was cut out for. He even had fun with it, saying (and I paraphrase from memory) that if, as was extremely likely, you couldn’t make it as a writer, you could be president of the United States (this was written back in the era when that was probably the world’s most respected job).

A more modern take on writing would be more like “O woe, writing sucks” (and then the person who wrote that profound thought goes on to whine about how they never get anything published).

My own take is somewhere along the middle path. While I accept that writing can be a grind, it also brings about great rewards. There are few feelings comparable to holding a book that contains something you wrote in it, if it’s there on merit (I have no clue how vanity publishing or self-publishing feels, as I’ve not really had experience there – for all I know, it’s awesome). The daily grind of rejection, on the other hand, is a very effective counterweight.

In my own case, the balance falls on the side of “keep writing”, so that’s what I do… but I often wonder if there isn’t another component: hope of immortality.

Before I look into the immortality game when it comes to writing, I wanted to say that I, personally, believe that all art is motivated, at least a little bit, by that dream of being remembered after you’re gone. Whether it be a commercially successful film director making a film to cement his critical reputation as opposed to raking in the dollars at the box office or a small child giving you a drawing (and crying if you happen to lay it on a table for a second), artists want one thing: to be remembered. Yes, approval at the time of creation and presentation is important, but it’s the legacy that matters more.

It’s deeply ingrained. A small child probably doesn’t have too much of a fixation on death or a true understanding of the stark fact that, someday, he will no longer be around, but even so, the instinct to live on through a piece of art is there.

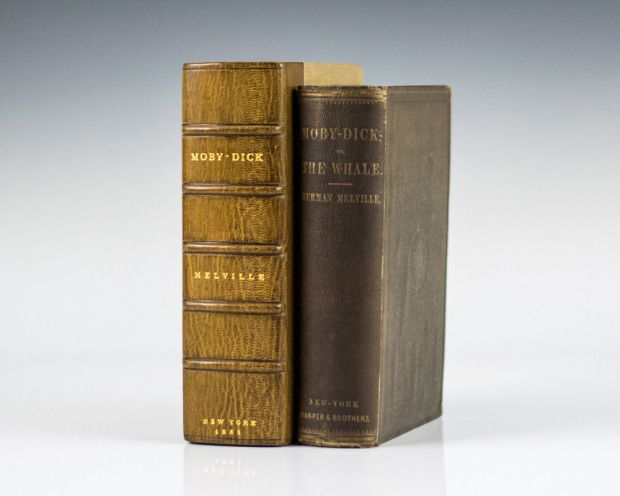

And, from the Lascaux Paintings to Moby Dick, that hope is sometimes fulfilled… more often, it isn’t, but the lightning in a bottle can happen.

I mention Moby Dick because, in literature, period popularity doesn’t necessarily track to immortality. Melville died believing Moby Dick was another failure in a career filled with them. Also believing he was a failure on the day he died was F.Scott Fitzgerald. And Poe, of course. Emily Dickinson’s poetry was, for the most part, discovered after her death (only about a dozen of her 1800 poems saw the light while she lived). Lovecraft and Howard are two men that the SFF genre anointed well after they were gone.

Of course, critical reevaluation and fame aren’t necessarily the rule. For every rediscovered author or poet who joins the canon once safely buried, there are ten that are universally accepted to be creating literary history as they write, a million who will never be recognized at all and a thousand whose bestsellers are no longer read by anyone (an amazingly interesting read is this page of bestsellers from a hundred years ago).

But writers who were establishing themselves forever were sometimes easy to spot. Dickens was writing history and everyone knew it. Harper Lee cemented her position in the pantheon and retired (well, mainly… let’s pretend Watchman never happened). Then there was Joyce, who established not only his reputation, but will, now and forever, define modernist literature.

But those are classic writers. Much more important to those writing today is the question: “So what about MY writing?”

Short answer? No one knows. Stephen King might be the next Dickens, a man whose work was wildly popular in its day and had staying power as the best reflection of an era, or he might be completely forgotten. The same could happen with the writers on the other end of the commercial spectrum (although it’s more likely that they will be forgotten, as there are less people around that would remember them).

Me? I always have this image of a scholar in 500 years or so coming across a brittle anthology containing one of my stories, a precious relic of the final days of print, and writing a misguided book-length dissertation on the way my characters reflect my subconscious manifestations of my desire to retire to a monastic existence on Ceres.

If that, or anything equivalent, ever happens, my work shall be done.